Scientists say cut soot, methane to curb warming — An international team of scientists says it has figured out how to slow global warming in the short run and prevent millions of deaths from dirty air: Stop focusing so much on carbon dioxide.

They say the key is to reduce emissions of two powerful and fast-acting causes of global warming — methane and soot.

Carbon dioxide is the chief greenhouse gas and the one world leaders have spent the most time talking about controlling. Scientists say carbon dioxide from fossil fuels like coal and oil is a bigger overall cause of global warming, but reducing methane and soot offers quicker fixes.

Soot also is a big health problem, so dramatically cutting it with existing technology would save between 700,000 and 4.7 million lives each year, according to the team's research published online Thursday in the journal Science. Since soot causes rainfall patterns to shift, reducing it would cut down on droughts in southern Europe and parts of Africa and ease monsoon problems in Asia, the study says.

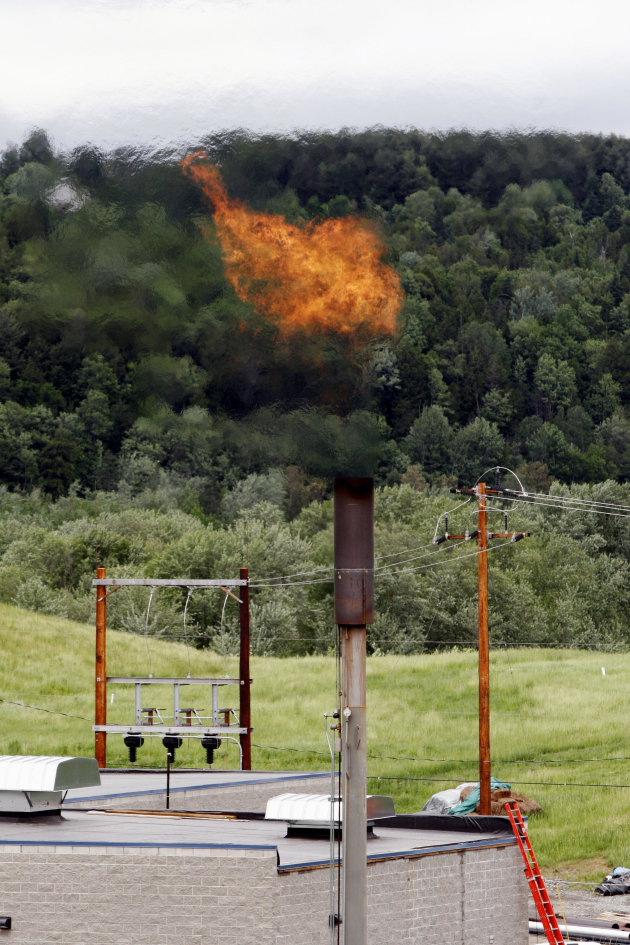

FILE - In this June 15, 2005 photo, methane gas burns off a stack near the Washington Electric Cooperative power plant in Coventry, Vt. An international team of scientists say they've figured out how to slow global warming in the short run, prevent millions of deaths from dirty air and increase food production. And it will save more money than it will cost. They say the key is to reduce emissions of two other greenhouse gases instead of carbon dioxide. Those pollutants are methane and soot. Those powerful gases are fast acting so reducing them would pay off quickly. Soot also is a big health problem, so cutting it would save lives. (AP Photo/Toby Talbot, File)

Two dozen scientists from around the world ran computer models of 400 different existing pollution control measures and came up with 14 methods that attack methane and soot. The idea has been around for more than a decade and the same authors worked on a United Nations report last year, but this new study is far more comprehensive.

All 14 methods — capturing methane from landfills and coal mines, cleaning up cook stoves and diesel engines, and changing agriculture techniques for rice paddies and manure collection — are being used efficiently in many places, but are not universally adopted, said the study's lead author, Drew Shindell of NASA.

If adopted more widely, the scientists calculate that would reduce projected global warming by 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius) by the year 2050. Without the measures, global average temperature is projected to rise nearly 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.2 degrees Celsius) in the next four decades. But controlling methane and soot, the increase is projected to be only 1.3 degrees (0.7 degrees Celsius). It also would increase annual yield of key crops worldwide by almost 150 million tons (135 million metric tons).

Methane comes from landfills, farms, drilling for natural gas, and coal mining. Soot, called black carbon by scientists, is a byproduct of burning and is a big problem with cook stoves using wood, dung and coal in developing countries and in some diesel fuels worldwide.

Reducing methane and black carbon isn't the very best way to attack climate change, air pollution, or hunger, but reducing those chemicals are among the better ways and work simultaneously on all three problems, Shindell said.

And shifting the pollution focus does not mean ignoring carbon dioxide. Shindell said: "The science says you really have to start on carbon dioxide even now to get the benefit in the distant future."

It all comes down to basic chemistry. There is far more carbon dioxide pollution than methane and soot pollution, but the last two are much more potent. Carbon dioxide also lasts in the atmosphere longer.

A 2007 Stanford University study calculated that carbon dioxide was the No. 1 cause of man-made global warming, accounting for 48 percent of the problem. Soot was second with 16 percent of the warming and methane was right behind at 14 percent.

But over a 20-year period, a molecule of methane or soot causes substantially more warming then a carbon dioxide molecule.

The new research won wide praise from outside scientists, including a conservative researcher who held a top post in the George W. Bush administration.

"So rather than focusing only on carbon dioxide emissions, where we have to make a tradeoff with energy prices, this strategy focuses on 'win-win-win' pathways that have benefits to human health, agriculture and stabilizing the Earth's climate," said University of Minnesota ecology professor Jonathan Foley, who wasn't part of the study. "That's brilliant."

John D. Graham, who oversaw regulations at the Office of Management and Budget in the Bush administration and is now dean of public and environmental affairs at Indiana University, said: "This is an important study that deserves serious consideration by policy makers as well as scientists."

The study even does a cost-benefit analysis to see if these pollution control methods are too expensive to be anything but fantasy. They actually pay off with benefits that are as much as ten times the value of the costs, Shindell said. The paper calculates that as of 2030, the pollution reduction methods would bring about $6.5 trillion in annual benefits from fewer people dying from air pollution, less global warming and increased crop production.

In the United States, Shindell calculates the measures would prevent about 14,000 air pollution deaths in people older than 30 by the year 2030. About 0.8 degrees Fahrenheit of projected warming in the U.S. would be prevented by 2050.

But health benefits would be far bigger in China and India where soot is more of a problem.

The study comes a day after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released the most detailed data yet on American greenhouse gas emissions. Of the emissions reported to the government, nearly three-quarters came from power plants. But with methane, it's different. Nineteen of the top 20 methane emitters were landfills.

Stanford University climate scientist Chris Field, who is a leader in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change but wasn't part of this study, praised the study but said he worried that officials would delay cutting back on the more prevalent carbon dioxide. Focusing solely on methane and soot and ignoring carbon dioxide "tends to exacerbate climate change," he said.

Another outside climate expert Andrew Weaver of the University of Victoria in Canada said the study is good news amid a sea of gloomy reports about climate change.

"This is a no-brainer," he said. "We have solutions at hand." ( Associated Press )

They say the key is to reduce emissions of two powerful and fast-acting causes of global warming — methane and soot.

Carbon dioxide is the chief greenhouse gas and the one world leaders have spent the most time talking about controlling. Scientists say carbon dioxide from fossil fuels like coal and oil is a bigger overall cause of global warming, but reducing methane and soot offers quicker fixes.

Soot also is a big health problem, so dramatically cutting it with existing technology would save between 700,000 and 4.7 million lives each year, according to the team's research published online Thursday in the journal Science. Since soot causes rainfall patterns to shift, reducing it would cut down on droughts in southern Europe and parts of Africa and ease monsoon problems in Asia, the study says.

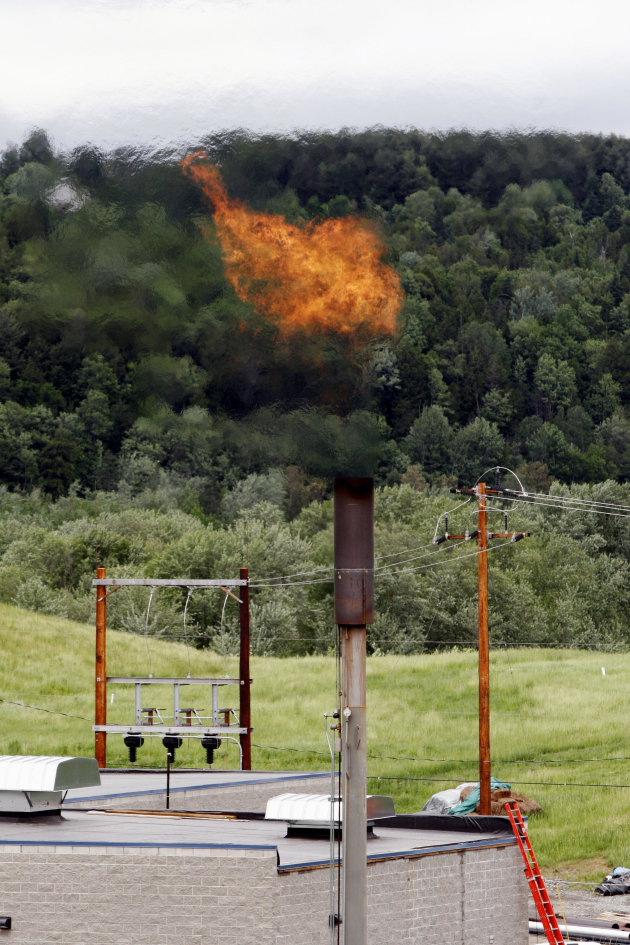

FILE - In this June 15, 2005 photo, methane gas burns off a stack near the Washington Electric Cooperative power plant in Coventry, Vt. An international team of scientists say they've figured out how to slow global warming in the short run, prevent millions of deaths from dirty air and increase food production. And it will save more money than it will cost. They say the key is to reduce emissions of two other greenhouse gases instead of carbon dioxide. Those pollutants are methane and soot. Those powerful gases are fast acting so reducing them would pay off quickly. Soot also is a big health problem, so cutting it would save lives. (AP Photo/Toby Talbot, File)

Two dozen scientists from around the world ran computer models of 400 different existing pollution control measures and came up with 14 methods that attack methane and soot. The idea has been around for more than a decade and the same authors worked on a United Nations report last year, but this new study is far more comprehensive.

All 14 methods — capturing methane from landfills and coal mines, cleaning up cook stoves and diesel engines, and changing agriculture techniques for rice paddies and manure collection — are being used efficiently in many places, but are not universally adopted, said the study's lead author, Drew Shindell of NASA.

If adopted more widely, the scientists calculate that would reduce projected global warming by 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius) by the year 2050. Without the measures, global average temperature is projected to rise nearly 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.2 degrees Celsius) in the next four decades. But controlling methane and soot, the increase is projected to be only 1.3 degrees (0.7 degrees Celsius). It also would increase annual yield of key crops worldwide by almost 150 million tons (135 million metric tons).

Methane comes from landfills, farms, drilling for natural gas, and coal mining. Soot, called black carbon by scientists, is a byproduct of burning and is a big problem with cook stoves using wood, dung and coal in developing countries and in some diesel fuels worldwide.

Reducing methane and black carbon isn't the very best way to attack climate change, air pollution, or hunger, but reducing those chemicals are among the better ways and work simultaneously on all three problems, Shindell said.

And shifting the pollution focus does not mean ignoring carbon dioxide. Shindell said: "The science says you really have to start on carbon dioxide even now to get the benefit in the distant future."

It all comes down to basic chemistry. There is far more carbon dioxide pollution than methane and soot pollution, but the last two are much more potent. Carbon dioxide also lasts in the atmosphere longer.

A 2007 Stanford University study calculated that carbon dioxide was the No. 1 cause of man-made global warming, accounting for 48 percent of the problem. Soot was second with 16 percent of the warming and methane was right behind at 14 percent.

But over a 20-year period, a molecule of methane or soot causes substantially more warming then a carbon dioxide molecule.

The new research won wide praise from outside scientists, including a conservative researcher who held a top post in the George W. Bush administration.

"So rather than focusing only on carbon dioxide emissions, where we have to make a tradeoff with energy prices, this strategy focuses on 'win-win-win' pathways that have benefits to human health, agriculture and stabilizing the Earth's climate," said University of Minnesota ecology professor Jonathan Foley, who wasn't part of the study. "That's brilliant."

John D. Graham, who oversaw regulations at the Office of Management and Budget in the Bush administration and is now dean of public and environmental affairs at Indiana University, said: "This is an important study that deserves serious consideration by policy makers as well as scientists."

The study even does a cost-benefit analysis to see if these pollution control methods are too expensive to be anything but fantasy. They actually pay off with benefits that are as much as ten times the value of the costs, Shindell said. The paper calculates that as of 2030, the pollution reduction methods would bring about $6.5 trillion in annual benefits from fewer people dying from air pollution, less global warming and increased crop production.

In the United States, Shindell calculates the measures would prevent about 14,000 air pollution deaths in people older than 30 by the year 2030. About 0.8 degrees Fahrenheit of projected warming in the U.S. would be prevented by 2050.

But health benefits would be far bigger in China and India where soot is more of a problem.

The study comes a day after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released the most detailed data yet on American greenhouse gas emissions. Of the emissions reported to the government, nearly three-quarters came from power plants. But with methane, it's different. Nineteen of the top 20 methane emitters were landfills.

Stanford University climate scientist Chris Field, who is a leader in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change but wasn't part of this study, praised the study but said he worried that officials would delay cutting back on the more prevalent carbon dioxide. Focusing solely on methane and soot and ignoring carbon dioxide "tends to exacerbate climate change," he said.

Another outside climate expert Andrew Weaver of the University of Victoria in Canada said the study is good news amid a sea of gloomy reports about climate change.

"This is a no-brainer," he said. "We have solutions at hand." ( Associated Press )

No comments :

Post a Comment